India

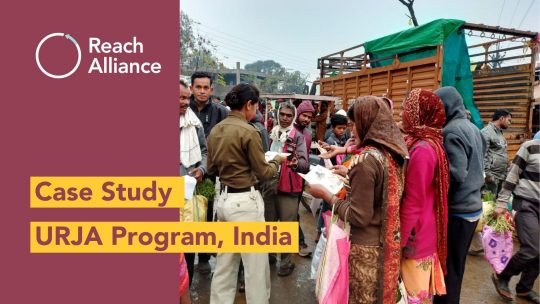

Addressing Violence Against Women in Madhya Pradesh, India: The Urgent Action and Just Relief Program

- Status

- Completed Research

- Research Year

- 2020-21

This case study examines the impact of Urgent Action and Just Relief (URJA) on improving women’s security in Madhya Pradesh, India. Studies show that police mistreatment in marginalized and resource-poor communities — particularly in the context of gender-based violence, where female victims are often blamed or challenged—leads to mistrust of police. Hierarchical police organizations also make it difficult to introduce new practices unless senior officials initiate new interventions and are involved in the implementation. Police training is especially challenging in low-income societies, where funding tends to be directed to more visible areas, such as improved police infrastructure and more officers on the streets. URJA is a policy intervention that aims to increase access to women’s police stations through the creation of help desks, establishing standard operating procedures, training to guide officers on cases involving women, and hiring additional female police officers. This report examines gender-sensitive policing.

Researchers

Mentors

-

University of Oxford

Maya Tudor

Associate Professor of Government and Public Policy; Director of Graduate Studies, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

-

University of Oxford

Akshay Mangla

Associate Professor of International Business, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

Related Information

-

How do women’s police stations help women report violence in India?

-

Science

Policing in patriarchy: An experimental evaluation of reforms to improve police responsiveness to women in India

-

How the Urgent Action and Just Relief Program addresses violence against women