Brazil

Reaching the Hard to Reach: A Case Study of Brazil’s Bolsa Família Program

- Status

- Completed Research

- Research Year

- 2015-16

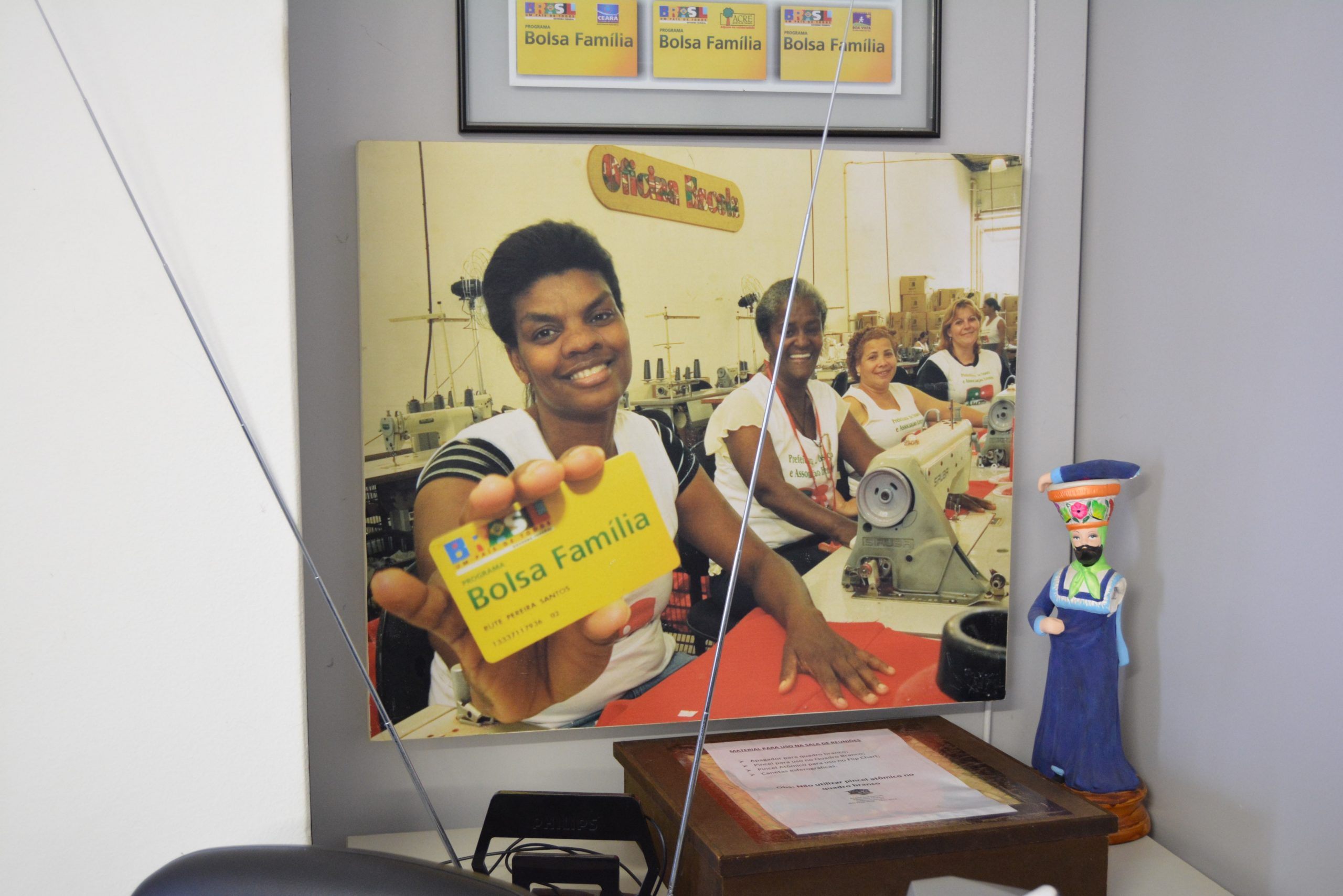

As the largest conditional cash transfer program in the world, the Bolsa Família Program, launched in 2003, currently provides income assistance to more than 14.28 million families through direct government-to-person electronic money transfers via the Caixa Econômica Federal. The program is impressive in its capacity to effectively reach families in the lowest income quintile through its active search (busca ativa) strategy.

Researchers

-

-

-

-

-

University of Toronto

Sarah Ray

Mentors

-

University of Toronto

Joseph Wong

Founder, The Reach Alliance; Professor and Vice-President, International, University of Toronto

Related Information

-

Reach Alliance Research Insights – Digital & Cash Transfers