Barbados

Barbados’s Trident: A Multipronged Approach to Combatting Childhood Obesity through Advocacy, Policy, and Education

- Status

- Completed Research

- Research Year

- 2022-23

Academic Institution

Project Collaborators

-

The University of the West Indies -

The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Barbados -

The Healthy Caribbean Coalition

Project Funder

The prevalence of childhood obesity among Caribbean children is much greater than in the rest of the world. In Barbados, 30 per cent of children are overweight and 14 per cent are obese. In response, Caribbean countries introduced the Port of Spain Declaration in 2007 to commit to noncommunicable disease prevention and control, including guidelines for physical education and healthy meals in schools to tackle and prevent childhood obesity. Despite Barbados’s commitment to reduce childhood obesity, a legal framework ensuring the presence of physical activity and nutritious meals in schools remains absent.

However, community recognition of childhood obesity as a significant issue has grown and prompted the implementation of grassroots initiatives. These bottom-up community approaches have integrated sectors across society, including school administrators and religious and charitable organizations, to deliver culturally sensitive methods to improve nutrition and activity levels in Barbadian children.

This report explores how the various community-led initiatives, schools, and government have contributed and interacted to prevent childhood obesity in Barbados. It also examines how the interventions led by different sectors have affected the population’s culture, habits, and actions surrounding obesity prevention, specifically through nutrition and physical activity.

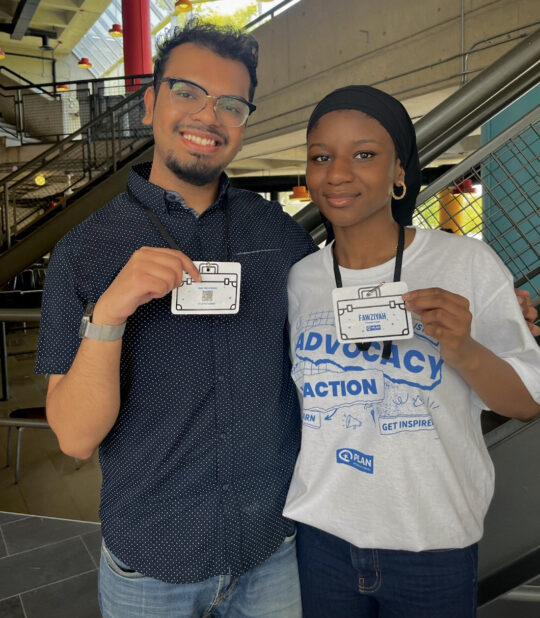

Researchers

Mentors

-

University of Toronto

Leanne De Souza-Kenney

Assistant Professor in the Human Biology Program and Health Studies Program, University College, University of Toronto