Philippines

APOAMF Low-Rise Building Project: Community-driven Housing Resilience for Informal Settler Families in the Philippines

- Status

- Completed Research

- Research Year

- 2022-23

In the Philippines, Metro Manila is increasingly vulnerable due to regular exposure to typhoons coupled with environmental degradation and loss of resources. Residents living in Pasig City typically belong to informal settlements with a lack of housing security and access to basic services, such as water and electricity. In response to this problem, residents united under The Alliance of People’s Organizations along the Manggahan Floodway (APOAMF) and worked with the National Housing Authority to construct the Manggahan Low Rise Building Project, climate-resilient and designed to withstand flooding. The case study will explore this housing solution in Pasig City, Philippines.

Researchers

Mentors

-

University of Toronto

Amy Bilton

Associate Professor, Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering; Director, Centre for Global Engineering, University of Toronto

-

University of Toronto

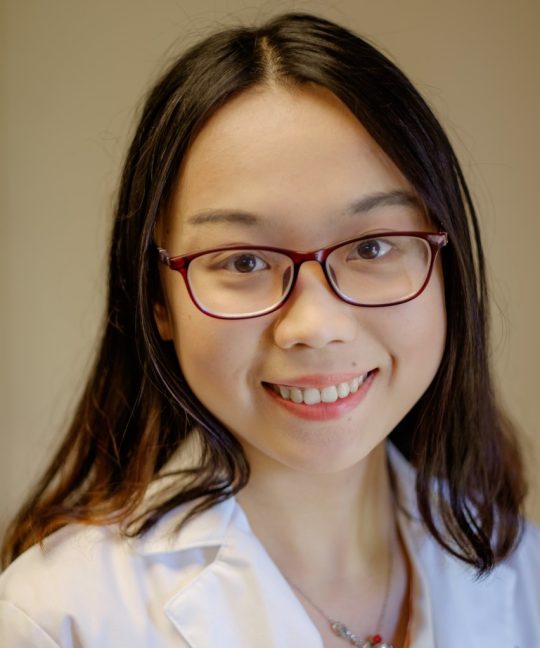

Sarah Haines

Assistant Professor in the Department of Civil & Mineral Engineering in the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering at University of Toronto