Polio’s History in India

Alongside Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria, India was one of the last countries in the world to report cases of polio. Between 1988 and 2014, the country went from having an estimated 200,000 cases in a year to being certified polio free by the World Health Organization (WHO). Over a span of more than twenty-five years, India consistently implemented and improved upon a national polio vaccination and preventative healthcare program that featured contributions from its government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Rotary International, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and WHO.

To achieve polio-free status, the government targeted funding and resources in two neighboring states that continued to report cases in 2008: Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. In 2009, they announced the 107 block plan that outlined a series of targeted interventions to address the social and geographic challenges in these remaining high-risk areas.

The polio program’s success was the result of motivated central leadership combined with comprehensive local commitment. The marriage of top-down decision making by the government, intermediary contributions from NGOs, and bottom-up interventions from local health workers created an environment that cultivated ownership, commitment, and change.

Bottom-Up Approaches: Interventions by Local-Level Health Workers

As the number of polio cases began to decline in India around 2008, eliminating the disease became more challenging. People with the remaining cases resided in the hardest-to-reach populations. They lived in the most geographically isolated areas, in groups that were constantly on the move, and among communities that were the most socially resistant to vaccination.

Community health workers comprehensively mapped every community in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, university students convinced local families that the vaccine was safe, and private health practitioners willingly agreed to report cases of paralysis to surveillance officers. Beyond any technical innovations, it was the local community members who tackled the unique challenges within each locality and made it possible to track and immunize the hardest to reach.

Surveillance

Availing itself of the expertise of the World Health Organization (WHO), India developed a robust surveillance system that made it possible to track high-risk groups and therefore respond to outbreaks and develop targeted strategies. Without this multilayered surveillance system, cases of polio among the hardest-to-reach groups were being missed, leading to continued transmission.

A Surveillance Structure to Track Acute Flaccid Paralysis

At the heart of any effective polio surveillance initiative is the need to track acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), which is characterized by muscle weakness and paralysis and is often caused by poliovirus in children. The rate of AFP detected by a country’s surveillance system serves as an indicator of its ability to detect polio. WHO guidelines state that a robust polio-surveillance system must identify at least two cases of AFP per 100,000 people. If symptoms of AFP are found in a child, labs test the child’s stool to confirm poliovirus as the source. Lab testing is necessary because AFP can also be caused by other diseases such as botulism, curare, and Guillain–Barré syndrome, although the poliovirus infection is one of its main causes. An effective AFP surveillance program thus requires comprehensive reporting of children with AFP symptoms, as well as adequate laboratory infrastructure for testing.

In 1997, the government and WHO established the National Polio Surveillance Project (NPSP) to conduct AFP surveillance. In each district in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, a government District Immunization Officer (DIO) and a WHO Surveillance Medical Officer (SMO) worked together to develop a comprehensive AFP reporting network that consisted of two tiers of reporting: large district hospitals and local community-level practitioners.

Larger healthcare centers (e.g., district hospitals, medical college hospitals, specialized pediatric hospitals) called reporting units (RUs) form the basis or first tier of AFP surveillance. When a child presents with AFP symptoms in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, the RU immediately reports the case to both the DIO and SMO. This redundant reporting to the government and WHO officials serves as a data-vetting mechanism. RUs are also required to send weekly reports to the DIO/SIO, even if no AFP cases were observed. These “zero reports” serve as an additional mechanism to flag deficient RUs and sensitize healthcare workers to look out for AFP. Because the RU reports the case only if a child presents there, surveillance is passive—if a child with symptoms presents to a smaller healthcare establishment that is not an RU, the case is not reported.

When it comes to more active surveillance, the DIO/SMO makes weekly visits to the highestpriority reporting sites: larger institutions and RUs that had been flagged for missing a weekly report. They check patient registers for any unreported cases, identifying any false reporting or training deficiencies among healthcare staff. While the larger healthcare facilities that make up Tier 1 serve as a starting point to catch AFP cases, they lack sensitivity. Solely relying on these reporting units comes with two major deficiencies.

Missing the hardest-to-reach cases. When the government tackles the so-called last mile of polio cases, outbreaks become less frequent. As the number of cases declines, the final remaining cases often occur in the hardestto-reach populations of people who are less likely to present at larger healthcare facilities. As a result, AFP cases that occur far away from larger healthcare centers are never reported and therefore continue transmission in hard-to-reach populations.

Delayed detection. To confirm poliovirus as the cause of AFP, labs must test stool samples within fourteen days of initial symptom onset. However, when a child in a hard-to-reach area experiences AFP symptoms, they need to be referred by a local

healthcare practitioner to a larger healthcare center where testing is available. By the time this happens, the testing window has usually already closed.

In developing an AFP surveillance system, establishing this first tier of reporting infrastructure was the easiest target because it involved making use of well-known, larger healthcare centers. However, creating a more sensitive surveillance system required finding individual, local-level practitioners where the hardest-to-reach AFP cases were often first reported.

To catch AFP cases in children who did not present to larger healthcare facilities, DIOs and SMOs developed a network of informers working at the community level. These included private physicians and local faith healers without formal medical training. This “informer” network was the key to a robust surveillance system because it allowed for the identification and timely stool testing of the hardest-to-reach children.

Initially, informers were hesitant to participate in AFP reporting because of its time demands and their concerns that the DIO/SMO would interfere with the treatment they provided. Unlicensed healthcare providers also feared being tracked in a database. To address these concerns, SMOs reassured informers that reporting would not interfere with their healthcare practices—all that was required was a simple phone call. Unlike RUs, informers were not required to send weekly reports as a matter of convenience. Instead, they were given the supervising SMO’s direct contact information so that AFP cases could be reported immediately.

Despite not receiving monetary compensation for their reporting, informers were also incentivized to participate through:

Training. Informers were given regular updates on the global polio-eradication effort and received AFP training through workshops that the SMOs provided.Access to lab results. After reporting a case of AFP, informers would receive the lab results. These informal medical practitioners who do not normally have the lab infrastructure to order these tests now effectively had diagnostic test results that would otherwise be unavailable to them.Recognition. WHO liberally gave informers certificates to recognize their involvement in the polio-surveillance effort, which they often displayed in their clinics. This involvement in a globally recognized program came with a sense of pride.

Figure 1. Tiers of AFP surveillance.Building the Informer Network through Health Facility Contact Analysis

Given the importance of the informer network in finding the hardest-to-reach AFP cases, how were informers, who themselves are hard to reach, identified in the first place? When a child with AFP presented to a facility that was already a part of the reporting network, the DIOs/SMOs completed a case investigation form and asked the family to identify all of the healthcare providers they saw prior to being referred to the reporting site. These providers were reviewed to determine whether they were already a part of the existing informer network. Any new providers identified during this process were visited in person by the DIO/SMO and recruited to be a part of the informer network.

In addition to the health facility contact analysis, DIOs/SMOs also consulted community stakeholders and healthcare providers already in the surveillance network to identify unknown informer clinics.

Social Mobilization Network: Using Creative Strategies to Find and Mobilize Groups

While surveillance was effective in tracking new polio cases, it provided little information about who was actually immunized in any given location. Tracking immunization status was the responsibility of the Social Mobilization Network (SMNet), an infrastructure of community health workers who operated in each high-risk community. Funded by UNICEF in 2002, the program was initially implemented across the high-risk areas of Uttar Pradesh before later expanding to Bihar in 2005. The mobilization network was managed primarily by UNICEF but received support from the government of India, the CORE Group, and later Rotary International and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

The SMNet program’s objectives were to promote access to information about the need for parents to vaccinate children, to increase immunization rates in high-risk areas, and to strengthen overall routine immunization. UNICEF was responsible for delivering SMNet’s communication strategies which were developed to overcome conspiracies, skepticism, and rumors that contributed to vaccine resistance.

SMNet Structure

The SMNet was a three-tiered structure of mobilization coordinators located at the community,ock, and district levels. At the local level, community mobilization coordinators (CMCs) were responsible for a group of 400 to 500 houses. They went door to door to speak with families and track the vaccine status of each child and household to create the most up-to-date microplans.

CMCs

The knowledge gained through the microplans gave researchers in-depth comprehension of the common reasons for resistance and exactlywhich houses still needed convincing. With this information, CMCs could approach individual families to have one-on-one conversations with parents. It was important for CMCs to be local, predominantly female, and often from the same religion and socioeconomic background as the families they spoke with. This facilitated the conversations because the women CMCs could develop trust and build relationships with mothers. For instance, if a particular community had a large Muslim population, the CMC would be the most effective if she also lived in the same geographical region, was Muslim, female, and spoke the same language as the households in her community. While the female CMCs were more likely to target mothers, there was still a small presence of male workers who spoke with the men of the house. A balanced approach was important to tackle resistance from both parental sides of the family.

Influencers

In addition to the responsibilities of CMCs, block mobilization coordinators (BMCs), and district mobilization coordinators (DMCs), “influencers” were also recruited to encourage vaccination and dispel rumors about it. Just as CMCs were local community members, influencers were also well-known in their communities, well-respected, and often trusted by parents. Influencers ranged from madrasa teachers and local shop owners to university professors. In some cases, a maulana (respected religious leader) promoting the vaccine was enough to convince a hesitant family. In other cases, it took the voices of multiple people (madrasa teachers, local media, and community health workers) to convince a family. An influencer was assigned for approximately every fifty houses and by 2016, there were over 49,266 influencers involved in SMNet.1

People were resistant for reasons beyond solely religious concerns. In Bihar, the most common reason families refused to take their children to polio rounds was that parents relied heavily on their daily wage jobs and were unable to take a day off to bring their children to health centers. Certain families also used polio vaccines as a bargaining tool to demand the construction of better roads in their villages before agreeing to vaccinate their children. The SMNet had to balance the community’s broader concerns and demands without letting the polio campaign turn into a bargaining tool.

Worker Motivations

CMCs, BMCs, DMCs, and influencers were dedicated to polio eradication in India. Some workers were passionate and motivated because they cared for the well-being of their community. They believed they were doing the right thing by informing families of the need to vaccinate. They felt a responsibility to help their communities and protect vulnerable children. CMCs saw value in their work because when mothers of resistant families became more educated, immunity rates also increased. By becoming a mobilizer they also gained credibility and importance. The workers were often treated with a greater level of respect in their own communities. Mobilizers also received training and were educated on important health initiatives and thus felt a sense of ownership and responsibility to convey the information to their communities. While they received some compensation, money was usually not a major motivating factor. That said, some workers were motivated to perform well in the hopes of being recognized by institutions such as the WHO and UNICEF and having an opportunity to join such organizations in the future.

SMet Communication Strategies

SMNet established an extensive communication strategy to promote parents’ awareness of the need to vaccinate their children. There were weekly meetings between the major partners— WHO, UNICEF, Rotary, and the government— to discuss the week’s primary challenges and the common themes among the cases of mass refusals. Partners explored strategies to address these problems which allowed for everyone to be on the same page. These meetings continued as partners had to actively brainstorm strategies to tackle each new challenge and form of resistance that arose.

There was also a Social Mobilization Working Group that met weekly and focused specifically on the communication campaign. The most effective communication strategies involved local, tailored, and customized messages aimed at each block that addressed their specific concerns. UNICEF and CORE worked closely together on communication strategies in Uttar Pradesh. For example, they educated local journalists on the polio campaign through workshops and lectures. The involvement of the local press and tailored advertisements were important to prevent the spread of false rumors. Celebrities were also used as a strategy, however their effectiveness for the last mile is debatable. While they may have helped in creating awareness of the polio campaign, a photo of a celebrity on a billboard was less likely to change a resistant family’s mind.

The information that CMCs gathered tracked the specific reasons for resistance so the working group could create customized messages to address the exact concerns on a round-by-round, district-by district, and village-by-village level. UNICEF and CORE each had their own CMCs collecting relevant data but agreed to work together in the field to avoid duplicating work or wasting resources.

Eventually UNICEF also recognized the importance of promoting behavioral change and incorporated strategies into the SMNet campaign. CORE played an important role in creating marketing material that promoted behavioral change to address practices that contribute to the spread of polio. The communication packages addressed simple issues such as the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, the promotion of regular hand washing, the importance of routine immunization and healthy nutrition, as well as strategies for diarrhea management. This communication strategy effectively allowed CMCs to discuss issues beyond vaccinations with hesitant mothers and families and it demonstrated their dedication to eliminate the likelihood of polio returning in any of their communities.

“Polio eradication is not a health success story. It is a communication success story,” a professor from Jamia Millia Islamia told us. The structure that SMNet put in place continues to be utilized in the delivery of Indian health services. For instance, the transition of previous SMNet resources now supports routine immunization led by the government. Similarly, the weekly working groups established through SMNet are being replicated at the national level to ensure efficient routine immunization.

A Network of Local Informers to Vaccinate Migrants and Understand their Living Habits

In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar there were many migrants who came to work in brick kilns, construction companies, and factories for approximately four months a year. This created a challenge for polio eradication because there was a higher incidence of poliovirus among migrant groups. When they traveled, migrant workers contracted and later spread the virus to areas where it was no longer endemic. While migrants were encouraged to keep their immunization cards and present them to immunization officers at their next destination, they weren’t always able to and the inconsistency created challenges for AFP surveillance and immunization records. As a member of an NGO framed the issue: “[brick kiln workers] don’t work during the summer so they return home. During the summer months, we don’t know where these workers have gone.” As a response, SMNet community mobilizer coordinators (CMC) were in charge of making microplans to provide vaccines to migrants and other high-risk groups.

“Polio eradication is not a health success story. It is a communication success story.”

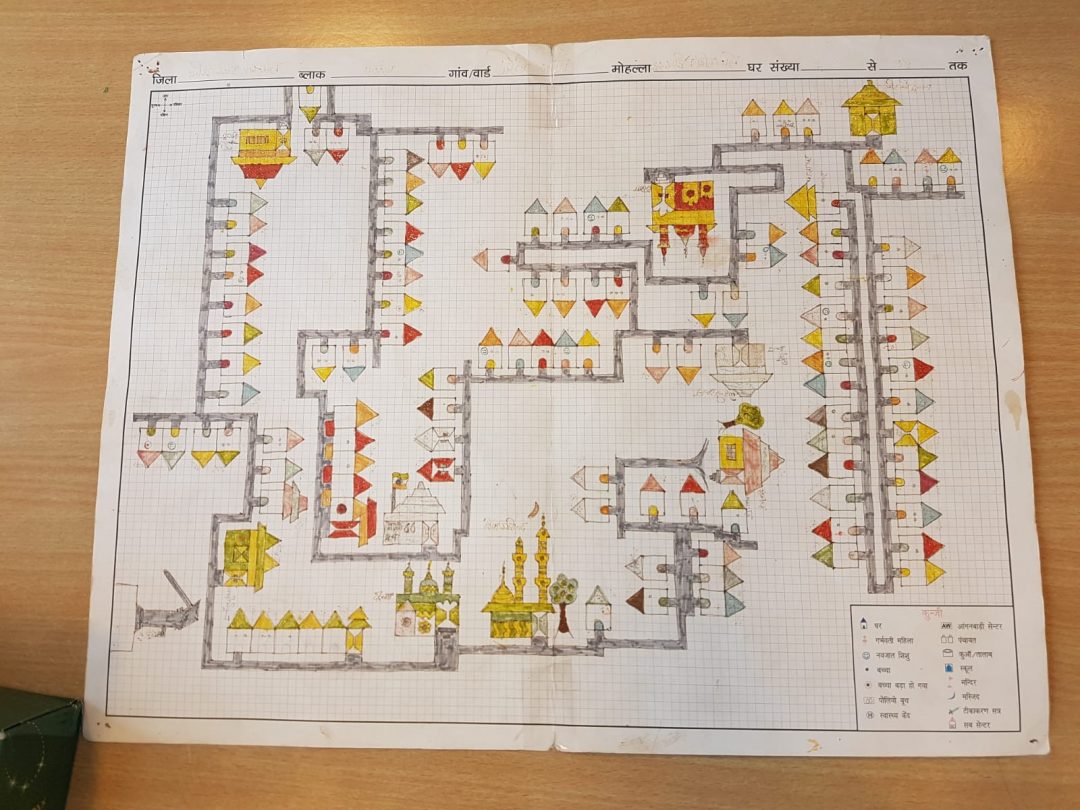

Figure 2. An example of a color-coded district micromap used by CMCs deployed by the CORE group when tracking houses.Micromaps

CMCs developed detailed community-level maps that showed the layout of houses and served to track immunizations per household. Community maps were aggregated into block-level and district-level maps. Apart from tracking houses and showing main infrastructure features, district maps color coded the presence of “high-risk groups” in an area. High-risk groups included brick kiln workers, construction workers, slum inhabitants, stone crushers, factory workers, nomads, and seasonal migrants living around rivers and flood plains.

Mobile Teams

In response to the high incidence of polio among migrant children, local community members were recruited to be part of mobile vaccination teams. These teams traveled to where migrants lived to vaccinate them. They consisted of a vaccine carrier, a marker, and a vehicle. Mobile teams had different registration forms than other teams to record the child’s name, parents’ names, and their district of origin. This information was useful for future planning.

Planning Around the Workers’ Daily Schedules

To vaccinate migrants’ children, SMOs and CMCs created microplans specific to each migrant’s occupation and typical daily schedule. The larger groups for economic migrants were construction workers, factory workers, and brick kiln workers.

Construction sites typically have fifty employees who live clustered around the site. During the day, workers are spread around the large area of the construction site. SMOs identified that the best time to vaccinate construction workers’ children was 8:00 am before the start of the work day when they could be found in a small campsite. (Because most community health workers are women, it would have been dangerous to send them after work hours.)

Brick kiln workers were the largest migrant group in the state of Bihar. They usually lived in small tents near the kilns. Vaccinating their children posed a greater challenge than working with construction workers because each brick kiln involved hundreds of workers. SMOs found it more efficient to vaccinate the children at the brick kilns instead of their place of residence. The workers’ schedule also changed depending on the weather. For example, in the winter, brick kiln workers started at 8:00 or 9:00 am whereas in the summer, they started at 5:00 am and came home at noon. On rainy days, workers typically did not work. With this information, community health workers were able to cater their vaccinations to the workers’ schedules.

Coordinating with Employer

The main strategy to vaccinate the children of migrant workers, the largest migrant group in Uttar Pradesh, involved talking to their employers. SMOs would contact the factory manager to coordinate a date and time to perform vaccinations in the factory. SMOs would send the employers a letter from a district government official mentioning the importance of polio eradication. Likewise, brick kiln supervisors cooperated with UNICEF because they understood the importance of polio vaccination. Brick kiln supervisors gave permission for on-site vaccination booths and provided a tally of families in an area. On the rare occasions that supervisors did not cooperate, BMCs contacted them for further discussions.

Validation

Of course, tracking migrants is difficult because they are constantly on the move. However, migrants often return to an area of residence seasonally and some informal living areas (e.g., empty lots) attract multiple migrant groups over time. To identify or “validate” these areas, community health workers walked through previous migrant points of residence twice a year. During the walk through, SMOs checked previous high-risk areas and identified new ones. Once a site was considered likely to attract migrants, it would remain on the validation list, except in cases where a construction project had been completed.

Migrant Tracking

Polio eradication in India involved a wide array of community health workers who sometimes had different styles of microplanning. Some health workers viewed migrant tracking as a cornerstone of the polio-eradication strategy. They studied historic migration patterns to predict the movement of high-risk groups. For example, they identified that in a Bihar brick kiln, the workers were from Eastern Uttar Pradesh and vice versa. CMCs and brick kiln supervisors would ask migrants where they were going next and then share this information with SMNet staff at the expected destination points. Because migrants would return to a location seasonally, CMCs and brick kiln supervisors planned for their return. Areas that were expecting migrants would have supplementary immunization activities.

Other health workers considered migrant tracking optional. They believed that the success of polio strategies involved moving away from the obsession with tracking. Regardless of where these migrant groups went, every community had a local vaccination plan that would ultimately find and mark every child who received polio drops with a black mark on their finger. As one health worker we met put it, “focus on ensuring that every kid in front of me has a black mark on his or her finger, no matter where they come from or where they go.”

Informers

SMNet benefited from local community knowledge to understand migrant movement. For example, SMNet officials from CORE and UNICEF trained community members in migrant-prone areas to become “informers.” When migrants arrived in an area, local informers were in charge of contacting CMCs. Informers were long-term residents who lived in high-risk areas—usually factory owners, brick kiln supervisors, barbers, or shopkeepers. They would therefore frequently be in contact with migrants and were trusted members of their communities. Apart from keeping track of movement, informers often convinced migrant groups to support vaccinations. By leveraging the expertise of people who were already influential in their communities, SMNet could locate migrants in a timely manner.

Transit Points

SMNet and vaccinators set up booths in areas that migrants commonly transited, including railway stations, bus stands, and even tourist sites like the Taj Mahal. For example, CMCs used train timetables to plan the best times to provide vaccinations. If there was a train arriving late, a team of vaccinators stayed in the station overnight. SMNet also targeted festivities such as religious festivals and weddings that brought in travelers. At these events, CMCs established contact with the travelers and brought them to the vaccinators.

Newborn Strategy

SMNet made a special effort to target newborns. Because many children in rural areas are not born in a hospital, there was no pre-existent mechanism to identify newborns. The challenge was therefore to identify and vaccinate newborns within the first seventy-two hours of birth. Prior to children’s birth, CMCs identified and visited pregnant women. CMCs had a different booklet to record information about newborns and kept a record of each child’s expected date of birth. After the birth, CMCs recorded each child’s name, date of birth, and date of vaccines administered. SMNet tracked the proportion of children who received vaccines right after their birth. There was also an OPV3 metric that demonstrated whether the newborn had received the three vaccines within the first few months of birth.

Creating Trust in the Context of Religious Division

Communication strategies played a large role in winning the trust of skeptics in local communities. In Uttar Pradesh, a key challenge in obtaining comprehensive polio coverage was reaching vulnerable, neglected, and minority populations. By 2005, polio statistics gathered by community health workers revealed that the minority Muslim population was overrepresented in polio cases. These minority members often had a poor sanitation infrastructure, a lack of investment for education and health care, and resistance toward vaccination. In response to these conditions, immunization implementers developed strategies to specifically reach these underserved demographics.

While initial efforts to immunize had reached most people, small pockets of resistance remained. Resistance presented in many different forms. Some households simply refused to open their doors to vaccinators. Others verbally intimidated health workers, accusing them of coming to their doorsteps to do harm.

Tackling Resistance

People who refused vaccines could mostly be categorized by vaccine hesitancy, social resistance, or cultural resistance. Vaccine hesitancy resulted from the lack of education about the vaccine’s purpose and safety parameters. Parents obtained medical information from multiple sources and struggled to make an informed decision in the face of contradictory information. For example, because of rumors, some parents felt that the vaccine would cause fevers. In other cases, cultural resistance rejects vaccination on the basis of religious opposition—members of this resistant group are wary of the cultural or religious implications of consenting to polio drops. Social resistance arose from marginalized and lower-class individuals mistrusting government intentions as a result of previous neglect involving social services’ delivery. While distinct, these ideas were not exclusive, and many cases of vaccine refusals involved multiple or all elements. One Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI) scholar said it well: “If the family has not had medical help from the government before, why would they suddenly trust the government to provide this particular health service?”

Education programs and friendly communication strategies addressed vaccine hesitancy. In other words, while this first tier of resistance was the most well-represented form, it was also the easiest to combat. Many in this category were open to the aid of trusted healthcare workers and CMCs at their doors. The second tier of resistance was socioeconomic resistance where in-group versus out-group mentality between lower classes and the government was more challenging to diffuse. In this case, the program had to prove that previously neglected people could trust NGOs and the government. Cultural resistance, the third tier of resistance, actually represented the fewest people but it was the hardest to overcome.

To tackle cultural resistance, the government and NGOs decided to collaborate with prominent Muslim institutions. Their mutual goal was to collectively promote behaviors that would stop the spread of polio. Members from institutions such as JMI, Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), and Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University were recruited to focus on advocacy and networking within Muslim communities to combat distrust of he vaccine. These institutions dispelled rumors about polio by working with local mosques and madrasas to promote healthcare literacy and advocate in favor of the vaccine. For example, one rumor was that the OPV was manufactured using pig blood which is deemed to be haram or forbidden in Muslim culture. To dispel this, influential Islamic leaders issued a fatwa (a ruling in Islamic law) to confirm that the OPV was halal. It confirmed that the components of swine blood in the vaccine were diluted to the point that it was acceptable for use.

Another example of effective advocacy by JMI was their production of The Green Book, an Islamic document that describes duty to health and family. The compelling arguments within this book came from a deep understanding of Islamic teachings and described the importance of ensuring child safety in the Muslim faith. The book uses religious reasoning to help motivate culturally resistant individuals to understand that vaccine refusal is an act of sacrilege while consent to OPV is not only compatible with Islam but also religiously favorable because compliance with OPV protects children. AMU staff would also apply this reasoning when convincing resistant families. For instance, one former AMU staff recalled being told that he should “remember the day of judgment, that we would both be there on equal footing,” and that he would be held accountable for his decision to push the vaccine. He responded by saying that he too would ask the person on the day of judgment “why they didn’t give the vaccine—why they let a child suffer.

Rotary also played a significant role in breaking down religious barriers to vaccine administration. Rotary formed the Ulama Committee made up of six prominent ulamas (highly respected Islamic scholars) who worked to support the polio campaign. The committee held events with district imams—local religious leaders—to address religious concerns about polio vaccines. During these discussions, references would be made to the Quran to provide religious justifications for the need to vaccinate children. This included emphasizing a parent’s duty to protect their child(ren) at all costs. Some imams in the past wrote articles fiercely opposed to vaccination, but advocacy from respected leaders now dissuaded them from doing so. Publicity was also a big part of these initiatives. For instance, one prominent ulama, Khaleed Rashid, vaccinated his own child at his meeting as a show of religious consent. Photos of this event were then circulated to local communities.

Socioeconomic resistance was a complex phenomenon layered in history, politics, and class relations. Historically, sterility politics and unequal social programming caused mistrust between Muslim and Hindu Indians. Many Muslims saw government family-planning programs as methods to control Muslim population growth. While Muslims were identified as an underserved population, they were not the only underserved demographic in the community.

Resistance against vaccination was also overrepresented in populations of lower socioeconomic statuses regardless of religious affiliation. A potential cause was the lack of diverse health services for these communities. With the ongoing effort and focus on polio as a single disease in the absence of other health services, suspicions of government intentions brewed. Many people found it hard to justify the importance of the eradication program’s continued funding, while services like routine immunization programs lacked support, and diseases like malaria were pervasive in local communities.

The involvement of AMU in 2002 helped address some of these concerns. AMU was well respected among the local Muslim community and had both the medical and scientific credibility to issue supportive statements. For example, AMU clarified rumors that there is no evidence of polio drops causing sterility. In this regard, certifications of its safety were produced and used in the communities to demonstrate that AMU had validated OPV as completely safe. These declarations were used at other Islamic institutions such as madrasas to encourage support for polio vaccinations. In this regard, one medical professor at AMU said, “If someone makes damage in a mosque (rumor), it can only be fought persistently by normal people, ordinary rational people. Ignore the rumor maker, and search for rational partners such as teachers.”

Figure 3. Different types of resistance toward polio vaccination that contributed to vaccine refusals. The arrows indicate that these behaviors can evolve or exist in combination.“Horizontal” Health Services

To address complaints from resistant families that polio vaccines were not tackling deep-rooted healthcare infrastructure issues, AMU began to take a more holistic healthcare approach. The approach was called “horizontal” health services. AMU began servicing local resistant communities for a wide variety of common medical complaints as a means to introduce vaccinations. By contrast, one of the weaknesses of the polio vaccination program is its characteristic as a vertical or topdown program that treats or prevents only a very specific disease. For this reason, departments such as Social Work (DSW) were mobilized to create projects that aimed to understand socioeconomic resistance. As part of the project, the university sent social work students into the field to engage with cases of vaccine refusals.

These students invited the hesitant household member for tea or coffee and had a conversation to build rapport while discussing polio. AMU also offered additional healthcare services to community members. This was defined in the “Underserved Strategy” at AMU where the university supported house-to-house efforts in converting household refusals. For example,physicians from the university would be available for contact by telephone call from the CMC if the family required an explanation about why the polio drops should be taken. Medical students from the Department of Community Medicine (DCM) were deployed starting in 2008 to work with front-line workers in mobilizing households. These students were often seen as legitimate healthcare professionals and provided free medications such as paracetamol to children with fevers or medical care for other common conditions.

Organizations such as AMU with the support of organizations like Rotary also used another method to create horizontal health services. Starting in 2006, health camps were organized by the DSW, DCM, and local hospitals once a month where families were invited to talk about their health concerns. Critically, doctors at these sites provided free medications to families. This outreach strategy involving holistic healthcare services in combination with vaccination efforts was more successful in gaining the trust of families than vaccination alone.

Summary

There were multiple barriers to polio elimination in India, social resistance toward vaccination being one of the most significant. Reaching impoverished regions also proved difficult because there was distrust between the population and the government after a history of neglect. The Social Mobilization Network (SMNet) structure of mobilization and a robust AFP surveillance system were utilized to tackle these barriers. A comprehensive information network was able to capture AFP cases earlier, provide support, and reach the hardest-to-reach areas.

Figure 4. Surveillance medical officers (SMOs) would often vaccinate children of laborers clustered around construction sites.Table 1. Role of the partners.By 2008, India was only two states away from polio eradication. District politicians, religious leaders, and local influencers became increasingly involved in the polio campaign and were often present at polio booths. Partner organizations also played a key role in eradication.

The all-party collaboration was effective thanks to a well-organized system and strong communication strategies. Each partner’s role was distinct and clearly established, which meant there was minimal overstepping of roles. The government recognized the need for NGOs’ involvement and cooperation to fill in all the gaps in their national strategy. Organizations such as UNICEF were given a significant amount of leeway to make decisions. The government’s willingness to include the public led to an increase in publicprivate partnerships in India, even beyond the health sphere. Whereas ground-level interventions by dedicated local actors (e.g., community health workers, students, physicians) allowed for the comprehensive tracking and immunization of polio, the country’s network of NGOs served as a crucial link between the larger governmental institution and smaller community players.

Top-Down Approaches: Strong Government Leadership

By taking ownership of the project and making it a national priority, the government of India played a major role in polio’s elimination. While the reasoning behind strong political motivation is multifaceted, the fact that the disease had already been eliminated in most countries by 2008 made it an important goal to achieve. With many of the major players in the field of international aid looking to India as proof of global health funding’s efficacy, polio elimination became an issue of national pride. The government played a strong role in the program’s planning, implementation, and success, especially in reaching the last cases. This leadership trickled down to local levels of government and also made international organizations more inclined to come on board.

Quality Improvement and Accountability Mechanisms

In collaboration with the WHO and UNICEF, the government developed a strong accountability and quality-improvement framework to ensure that the polio program was implemented effectively. This was important because it addressed gaps in training as well as issues with falsification and underreporting of data during the program’s early stages.

For example, there were instances where vaccination data suggested that immunization coverage was high in certain areas when in fact the numbers were being misreported or falsified. These mistakes during reporting were not always ill willed—physicians and community health workers were under significant pressure by officials to meet immunization targets and produce positive results.

To address these issues, a task force was established to monitor surveillance and immunization activities in every district. These district task forces were chaired by a government-employed district magistrate (DM) and included local physicians and various district-level officials, such as chief medical officers (CMOs), surveillance medical officers (SMOs), district immunization officers (DIOs), and social mobilization network (SMNet) mobilizers. District task forces held frequent meetings during vaccination rounds where the SMNet (affiliated with UNICEF) and the National Polio Surveillance Project (NPSP, affiliated with the WHO) officials provided an update based on surveillance and immunization data. By having data-verification systems in place to ensure accurate reporting, the government could identify deficiencies in training or cases of false reporting. There were checklists and clear indicators that were frequently reviewed by workers’ direct supervisors to monitor progress and avoid underperformance.

An example of this is the double-checking mechanism that was used to verify vaccine refusals. The DIO would compile a report based on data from a team of front-line workers who visited all of the houses in a community and recorded refusals. Concurrently, the SMO would create a separate report by hiring a group of independent monitors to double-check the same houses in a community. If the findings differed when these reports were presented to the district magistrate (DM) at a district task force meeting, the DM identified the source of the discrepancy and developed immediate solutions.

For instance, if monitors determined that frontline workers required more training, the DM temporarily stopped immunization activities to provide additional education and reorient teams. If information was falsified, the DM held those at fault accountable. Workers who falsified information were made to redo training or repeat entire rounds of house-to-house microplanning. In certain cases, physicians even lost a day of salary or were publicly shamed during district task force meetings. Ultimately, while NPSP and SMNet officials were instrumental in providing data and highlighting problem areas, the DMs were responsible for providing leadership and guidance and holding workers accountable.

Decision Making, India Expert Advisory Group, and the MOPV Debate

With such a large number of stakeholders involved, the coordinated polio-elimination effort in India was a result of the government’s strong leadership. In 1999 they formed the India Expert Advisory Group (IEAG) for polio eradication, which featured representation from multiple government ministries, Indian researchers, as well as international stakeholders (e.g., WHO, UNICEF). The IEAG held periodic meetings and played a key role in monitoring progress and developing recommendations that informed the government’s decisions.

The impact of the government’s decision making and the IEAG’s influence was illustrated in 2005 during the transition from a trivalent oral polio vaccine (tOPV), which provided immunization against type 1, type 2, and type 3 poliovirus, to a monovalent oral polio vaccine (mOPV), which provided immunization against only a single type of poliovirus. The government made a series of decisions that were initially met with criticism but that eventually paved the way for polio’s elimination.

In the mid-2000s, despite high tOPV coverage in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the trivalent vaccine’s poor efficacy led to continued wild polio virus (WPV) transmission. Children who had received more than seven vaccine doses were still getting polio.

In 2005, a potential solution to this problem was developed. As an alternative to tOPV, monovalent OPV type 1 and type 3 was licensed based on a study that showed that these vaccines had between two and a half and three times greater efficacy than the trivalent vaccine. The government had a difficult decision to make. Although switching coverage from tOPV to mOPV1 and mOPV3 seemed like the obvious solution, there were two major risks that had to be considered.

Simultaneous mOPV administration . Although the monovalent vaccines had been shown to be more effective than the trivalent vaccine when given individually, researchers were still unsure whether giving both mOPV1 and mOPV3 at the same time would compromise their efficacy. Operational complexity. Giving both vaccines at once presented a significant operational challenge. Up until this point, the 2.3 million polio vaccinators in the country were giving only one oral vaccine dose per person in each campaign. Requiring vaccinators to differentiate between vaccine vials would add an extra layer of complexity.

With these challenges in mind, the government— with the recommendation from the IEAG— decided to prioritize WPV1 in 2006. This alleviated the issue of having to provide both monovalent vaccines at the same time but came at the risk of increased susceptibility to WPV3. This risk was justified because the IEAG believed that WPV3 would be easier to eliminate even if antibody seroprevalence was low. This was not the case for WPV1, which was the more frequent cause of paralytic disease and thus a priority.

As many critics surmised, WPV3 outbreaks occurred in 2007 and 2009. Despite the controversy and questioning that the government encountered, they remained steadfast in the strategy laid out by the IEAG. Eventually, WPV1 was brought under control and WPV3 cases declined quickly thereafter. It was because of this leadership and strong decision making that the country was able to navigate the uncertainty associated with vaccine efficacy to eliminate polio.

Summary

Rather than completely overhauling India’s polio program, the government’s commitment to quality improvement and accountability brought about the disease’s successful elimination. Achieving more comprehensive vaccination against polio was less about making drastic technological advancements and more about small, incremental changes to a system that already existed. Improvements such as the development of a redundant polio case reporting system and the implementation of regular district meetings chaired by government officials who placed an institutional priority on accuracy and accountability ultimately led to the country’s success.

With such an easily communicable disease threatening a country with a population as large as India’s, it was the government’s ability to make quick and decisive adjustments that led to polio’s elimination. This strong decision making

Lessons Learned

The elimination of polio in India has had a lasting impact on the country. Not only has it served as proof that disease elimination in such a large country is possible, but many of the strategies that were developed throughout the years created an outline for future vaccination efforts. Here are some of the lessons that polio elimination has taught the global community

Holistic Approach to Health Care

Community health workers went into people’s homes and listened to their various grievances about different diseases and sanitation problems in their communities. People in hard-to-reach communities often felt that they had more pressing problems than polio, which was viewed as a non-life-threatening disease. Many of the vaccine-resistant people did not have access to health care or had never been visited by a community health worker prior to the vaccinator. When a doctor came into the village, there would be a line of people waiting for him or her with other health concerns. Through programs like the underserved strategy, the Social Mobilization Network (SMNet) created trust with families and provided horizontal health care.

Strong Government Leadership at the National Level and Ground-Level Partnership

Nonstate actors were invaluable in the funding, planning, and detailed implementation of polio eradication in India. They designed strategies to avoid replication of tasks. While these organizations influenced decisions, the Indian government had the final decision-making power. Polio eradication required a strong-willed government that was willing to spend resources on these strategies.

The Art of Microplanning

During the initial years, there was a lack of accurate data reporting polio vaccinations. Starting in 2001, community health workers collected the needed data. Microplanning made certain communities more visible to the government. For many people in rural areas or slums, it was the first time they were visited by a government health official. Polio eradication’s microplans have since been used for subsequent health programs, creating a long-term impact on India’s healthcare system.

You Trust People Like You

When the polio campaign started, many of the community mobilization coordinators (CMCs) were men. However, mothers were usually the parent in charge of children’s health. Soon, UNICEF realized that male CMCs were not being allowed inside the houses so they hired women as CMCs. Female surveillance medical officers (SMOs) or CMCs would go to the houses at times when men were away so that mothers could voice their concerns about the vaccines openly. As a former community health worker said, “If they [fathers] were there the women would speak very low and would not convey any information.”

Although there was increasing resistance to vaccines in the Muslim community, in the early years of the polio campaign most of the community health workers were Hindu. This contradiction was addressed in the underserved strategy, where Muslim social workers and medical students discussed vaccination with resistant families. In some cases, microplans included the area’s predominant castes in order to send CMCs of the same caste. Over time, policy planners realized that it was easier to assuage vaccine hesitancy when participants identified with the community health workers.

Replicability; Not all Diseases are the Same

Many health practitioners in India think of measles as the next disease to be eradicated. With the support of the World Health Organization (WHO), the government launched a two-year measles-rubella vaccination campaign in 2017. However, compared to polio a major challenge in eradicating rubella is the lack of a non-injectable vaccine. Having oral vaccines for polio created an opportunity to have a massive force of community healthcare workers. As previous community health workers argued, “you can’t create the same manpower around anything else.” Non-injectable vaccines meant vaccinators did not need high levels of education or qualifications. Training for polio vaccinators was short—approximately one day. By contrast, injectable measles-rubella vaccines pose a greater logistical challenge.

Is Eradication Really the Goal?

In the years leading up to eradication, polio was India’s top health priority. While the eradication strategy has a long-term impact, other health programs received less funding and resources during that period. Many health professionals felt that polio eradication created chaos in the country’s healthcare system and that the focus should shift from eradication to disease control.

Conclusion

For India to accomplish polio elimination, simply having the technical capacities available was insufficient. Instead success stemmed from the combination of partnerships within local communities and strong central leadership united by the vision of polio elimination as the end goal. Both top-down and bottom-up strategies involved significant coordination made possible only by the commitment and motivation of all parties involved. For countries currently in the process of disease elimination, India demonstrates that although resources and technical expertise play significant roles, elimination cannot be accomplished without strong political will and leadership, as well as local participation and a mandate that unifies local communities to be able to do that.

Figure 5. Mobilization planning maps at the community, district, and block levels.Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through the Reach Alliance, a partnership between the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth . Research was also funded by the Canada Research Chairs program and the Ralph and Roz Halbert Professorship of Innovation at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy. We are grateful to have had the opportunity to speak with and learn from those we met and interviewed in India.

This research was vetted and received approval from the Ethics Review Board at the University of Toronto.

MASTERCARD CENTER FOR INCLUSIVE GROWTH

The Center for Inclusive Growth advances equitable and sustainable economic growth and financial inclusion around the world. The Center leverages the company’s core assets and competencies, including data insights, expertise, and technology, while administering the philanthropic Mastercard Impact Fund, to produce independent research, scale global programs, and empower a community of thinkers, leaders, and doers on the front lines of inclusive growth.

MUNK SCHOOL OF GLOBAL AFFAIRS & PUBLIC POLICY

The Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at the University of Toronto brings together passionate researchers, experts, and students to address the needs of a rapidly changing world. Through innovative teaching, collaborative research, and robust public dialogue and debate, we are shaping the next generation of leaders to tackle our most pressing global and domestic challenges.